Welcome to the Hardcore Husky Forums. Folks who are well-known in Cyberland and not that dumb.

The Chump Effect

Comments

-

Sort of agree. But I have no desire to pay for a 20 year olds intellectual interest. Let the banks back in to fund student loans along with allowing for bankruptcy. There goes at least half the current student loans. Banks will finance an engineer or CPA. Won't touch an ethnic studies major.Pitchfork51 said:

Intellectual interest as a 20 year old is fucking stupid though. Get in and get the fuck out.creepycoug said:

Partially agree.Pitchfork51 said:My issue with it is that this doesn't solve anything without first putting in policies that make it clear that all of this was a bad mistake

It seems to be conspicuously missing. No one is saying if you need relief it's because you clearly did a bad thing. Its more like "you did right but the world is evil"

Part of it is that for 2 generations now people have been brainwashed that if they go to a "good school" (no matter the debt, major etc) then they are entitled to a good job and life.

The colleges, teachers, and people's own shitty parents (biggest culprit) are the enablers

That needs to end too.

If you go to a "good school", and use that education to go make money, honestly, six figures of debt is nothing that early in life.

I speak from experience. I didn't go to LS at UPenn, at a time when tuition was about $20K a year, and they had given me $10k/year in free money. In the early 90s, I was afraid of, let's call it, $60k of debt. So I stayed here and graduated with zero debt. In the intervening time, I've pissed away $60k a few times on non-sense. I should have gone to Penn.

The other thing to remember is that the "good school" often allows you to study what is of actual intellectual interest to you. A friend's daughter was just profiled in one of those Sillicon Valley "Under 30 rising stars". Dartmouth AB History. -

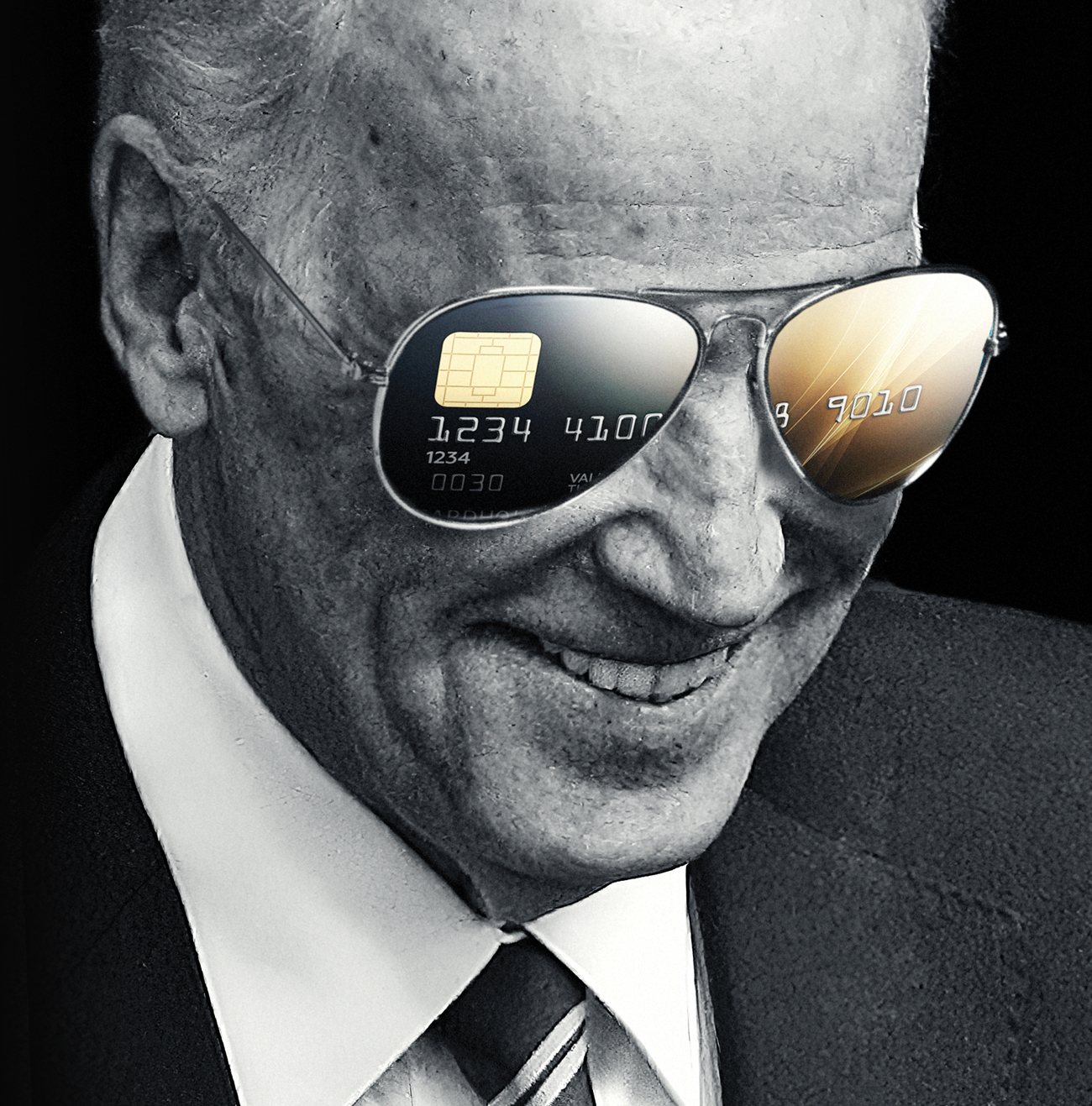

Maybe Joe can get to work on credit cards and the 20% plus interest they charge? Oh and look - student loans!

https://motherjones.com/politics/2019/11/biden-bankruptcy-president/

Though he’s now a millionaire thanks to book sales and speaking fees, Biden has long positioned himself as the champion of the middle class, a scrappy kid from Scranton who’s fought the good fight for decades. His adopted home state is part of that identity too—an unglamorous enclave of scrapple and toll roads, the Acela Corridor’s own Flyover Country. But as he pursues his third and likely final quest for the Democratic presidential nomination, his record haunts him, because the interests of Delaware are often at extreme odds with everyone else’s.

Biden did not create this system, but he used his influence to strengthen and protect it. He cast key votes that deregulated the banking industry, made it harder for individuals to escape their credit card debts and student loans, and protected his state’s status as a corporate bankruptcy hub.

Biden’s career in the Senate placed him on the wrong side of some of the biggest financial fights of his generation and brought him into conflict with some of the same rivals he faces today. If you want to understand how Biden became Biden, you have to understand how Delaware became Delaware.

When the economy sagged in the late 1970s, the cash-strapped state began looking for ways to supplement its income. In 1981, it passed a new law, written by banking lobbyists and backed by DuPont, with the hopes of becoming, in the words of the governor who signed it (a du Pont, naturally), “the Luxembourg of the United States.” While other states were setting caps on usury rates, Delaware told banks they could charge whatever they wanted in annual interest and late fees; the banks could also foreclose on debtors’ homes if they fell behind on payments. The state even cut corporate taxes.

The result was a corporate gold rush. A dozen companies, including JP Morgan and Chase Manhattan (now JP Morgan Chase), opened offices in Delaware in the first year alone. By the late ’90s, four of the five largest credit card firms in the country had set up in Wilmington, and the industry employed at least 35,000 people. The Company State had pulled off a lucrative turnaround.

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, as Biden settled into a comfortable incumbency, banks sought to make the rest of the country work more like their mid-Atlantic refuge—to embrace the least possible amount of regulation so they could grow as big as they wanted. Delaware, for instance, had a loophole allowing banks to sell insurance. Now the banks wanted to do that everywhere. Delaware’s laws made it easy for credit card companies to do business in any states they pleased. Financial firms wanted regular deposit banks to have that ability too.

Biden supported a baby-step deregulatory effort in the early 1980s, and then, in 1994, he backed a very big one: the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act, which eliminated the remaining barriers to where banks could operate. The law passed with overwhelming bipartisan support and was fairly innocuous in some respects, codifying changes that were already happening at the state level. But it opened the floodgates to an era of corporate consolidation. Delaware’s financial institutions got another big boost in 1999, when Biden voted for the Financial Services Modernization Act, which repealed the Depression-era Glass-Steagall law barring banks from owning securities and insurance businesses. By 2016, there were almost 5,000 fewer banks in the United States than there were two decades earlier, and the 10 largest firms controlled half of all banking assets.

-