Welcome to the Hardcore Husky Forums. Folks who are well-known in Cyberland and not that dumb.

Beijing sees an opportunity in Europe’s disagreements over how to manage Chinese relations

DerekJohnson

Administrator, Swaye's Wigwam Posts: 70,337

in Tug Tavern

By: Antonia Colibasanu

Geopolitical Futures

Earlier this month, a diplomatic row erupted between China and an unlikely European nation. It began back in May, when Lithuania decided to leave the 17+1 initiative, a project established in 2012 by Beijing to strengthen ties to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Then, in July, the government in Vilnius said it would allow Taiwan to establish a representative office in Lithuania under its own name, rather than “Chinese Taipei,” a decision Beijing criticized as a violation of its “one China” policy. In response, on Aug. 10, Beijing recalled its ambassador to Lithuania and asked that Vilnius recall its ambassador to China. A week later, it also suspended freight train service to Lithuania.

This may seem like a minor spat between Beijing and a relatively minor European country, but as a member of the European Union, Lithuania’s foreign policy moves have broader implications for the bloc. Its dispute with Beijing could make it harder for the EU to reach consensus on how to manage its relationship with China. But for Beijing, that’s a good thing. It benefits from divisions that prevent the EU from forming a unified front against it. That’s why, even as its relations with the Baltic states grew increasingly tense, its relations with other EU members – namely, Hungary and Poland – as well as the Western Balkans were getting stronger. In these places, China sees an opportunity to expand a growing wedge and strengthen its foothold in Europe.

China and the EU

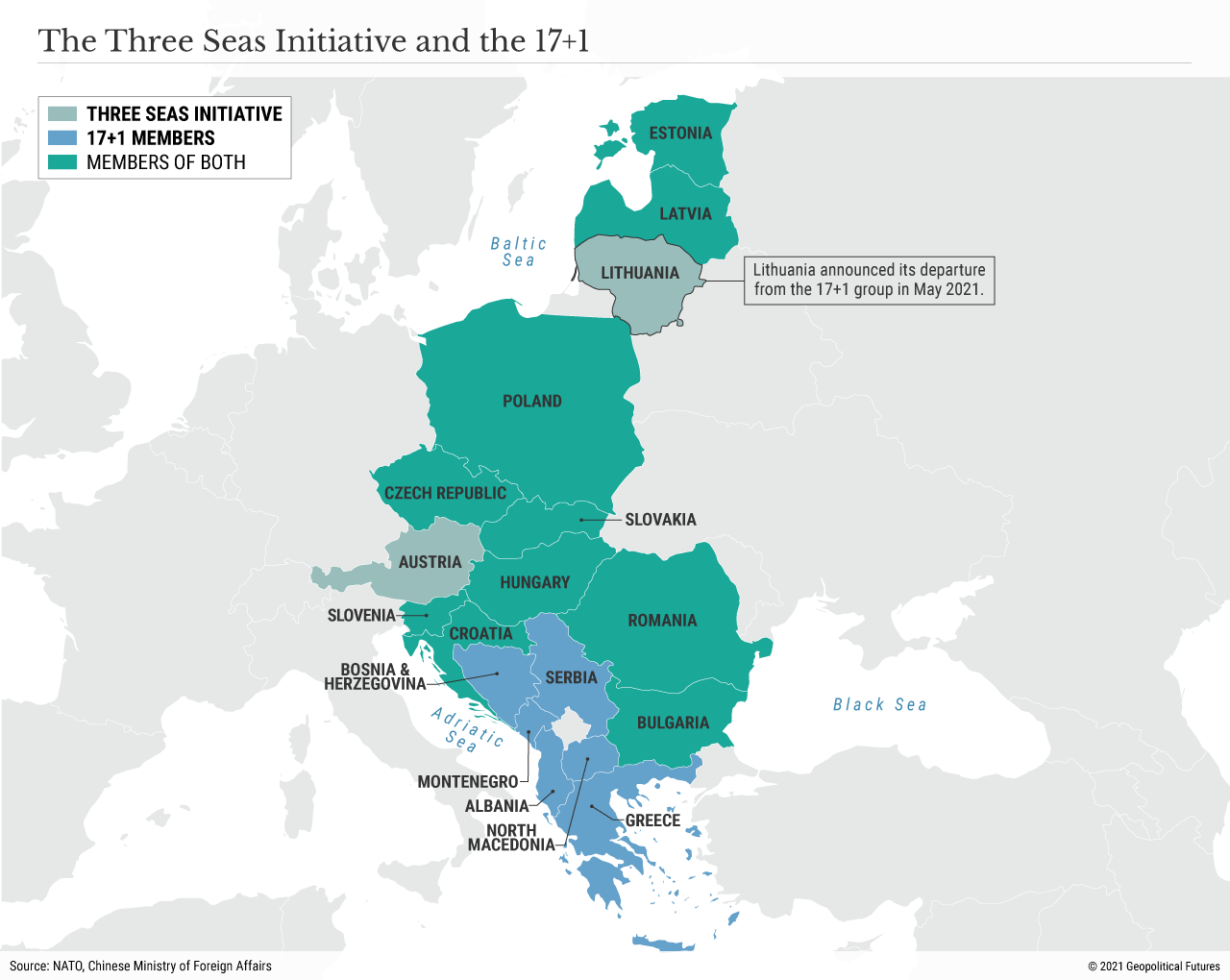

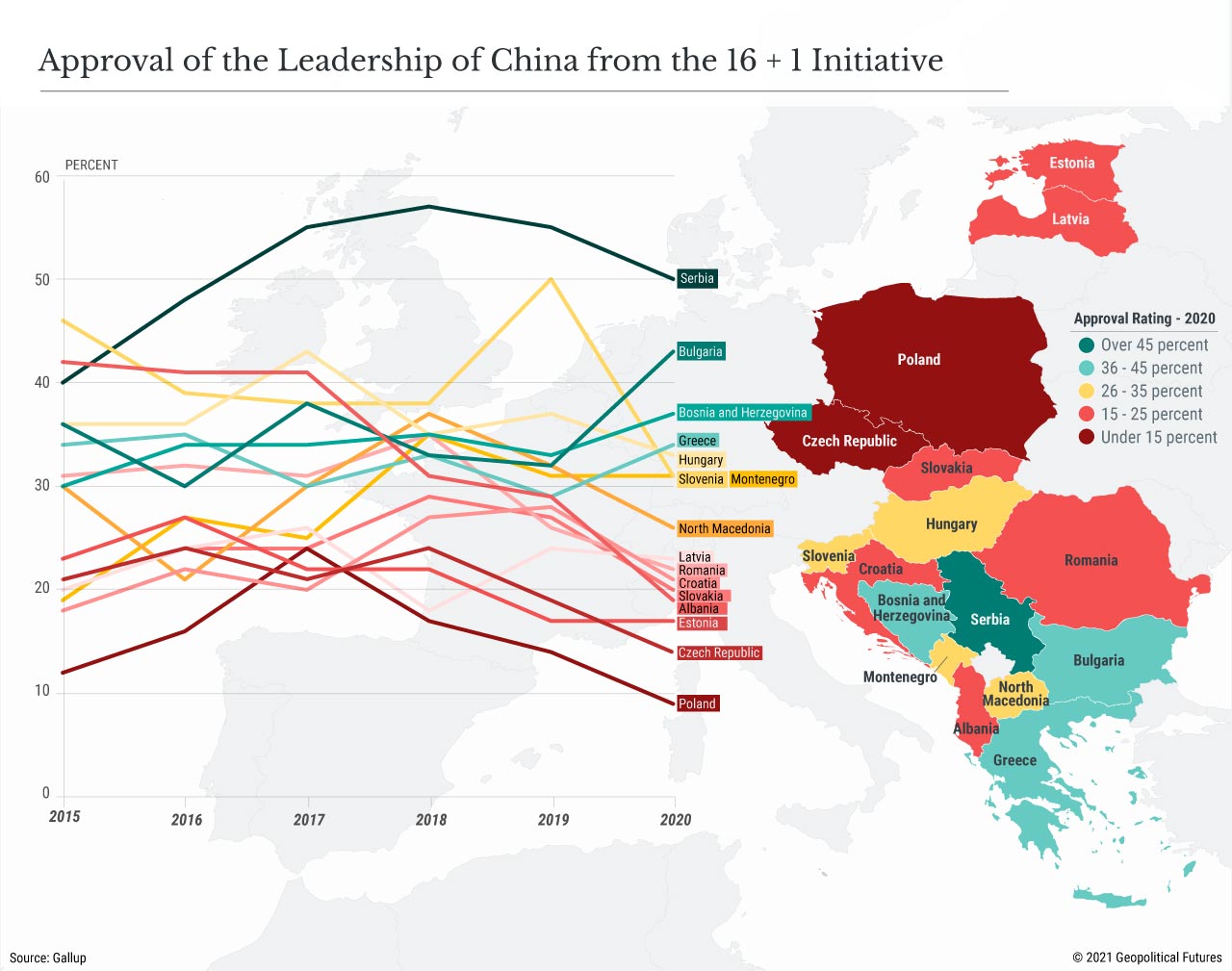

Under China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative, the 17+1 format was designed as a way for Beijing to build economic ties to Central and Eastern Europe through investments and promises of better access to the Chinese market. Since the program's inception, however, China’s involvement in the region hasn’t been balanced across all the participants.

The project includes many of the same countries involved in the Three Seas Initiative, a NATO-backed alliance spanning the Baltic, Black and Adriatic seas focused on strengthening regional cooperation. The Three Seas project supports the development of economic infrastructure – financed by private and public (including EU) funds – that’s critical to NATO’s strategy to counter Russian influence along its current containment line. For China, therefore, the 17+1 initiative was a way to balance other external powers that already had a strong foothold in the region – mainly the EU but also Russia and the United States.

Beijing has been eager to partner with European countries that want to keep their foreign policy options open. Chief among them has been Hungary, which is likely China’s closest ally in the region. Earlier this month, Budapest awarded two Chinese firms – China Civil Engineering and China Railway 11th Bureau – contracts to complete upgrades on a railway connecting Hungary to Serbia – just the latest Hungarian deal for Chinese financing. Hungary is an important ally to China because of its willingness to defy Brussels on a number of fronts. Hungary has a long history of balancing between powers – most notably the West and Russia, but increasingly also China. By avoiding siding with one power over any other, Budapest has found that it can reap the most benefits.

Poland is another country with which China is developing closer ties. Like Hungary, Poland has had a contentious relationship with Brussels over issues relating to the rule of law and EU values. In the past, Poland has been wary of getting too close to China because of its strategic relationship with the United States, but since the start of this year, its relations with Beijing have improved. According to the Polish Economic Institute, Poland was among the top destinations in the EU for Chinese investment in 2020, totaling an estimated $1 billion. Bilateral talks have also intensified. Polish Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau visited China in late May – just weeks after the U.S. waived sanctions on a consortium tasked with building the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, a project that will bring Russian natural gas to European markets and that Poland opposes. Warsaw’s overtures to Beijing are meant to send a message to Washington that it needs to continue to engage with its traditional allies in Eastern Europe.

The timing of Rau’s visit, just after Lithuania announced its decision to leave the 17+1 grouping, was convenient for China. It allowed Beijing to stem the fallout from the announcement and prove that it’s still engaged in the region. For China, building ties to Poland is only one element of a broader strategy to rebalance its increasingly uneasy relationship with the EU and keep the public engaged with the Communist Party’s agenda internally.

Lithuania said its decision to pull out of the initiative stemmed from the fact that it didn’t see any increase in access to the Chinese market, despite Beijing’s promises. That China is not among Lithuania’s top trading partners made it easier for Vilnius to make the move. Other EU members have also signaled their displeasure with the initiative – Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Romania and Slovenia chose to send ministers instead of heads of state to the last 17+1 summit in February – but none have left the group so far.

Lithuania’s spat with China had been brewing for a while. Last November, its parliament voted to replace Chinese tech firm Huawei with Sweden’s Telia Company in the country’s 5G network, and in May, the parliament passed a resolution condemning Beijing’s treatment of Muslim minorities as “crimes against humanity.” The resolution came two months before Lithuania announcement it would allow Taiwan to open a representative office under its own name in Lithuania.

Why would Vilnius choose to take a stand against Beijing now? In part, it’s because Lithuania is concerned about Beijing’s growing interest in its neighbor, Belarus, which is not part of the now-16+1 initiative. Since 2015, China and Belarus have grown closer both economically (through the provision of Chinese loans) and politically. Last year, Chinese media followed Russian media in characterizing mass anti-Lukashenko protests as an attempt at a Western-backed “color revolution.” Chinese media were also critical of the EU’s decision to impose sanctions on Belarus after its forced landing of a commercial plane en route to Lithuania in Minsk to arrest a dissident journalist. Lithuania has long been a staunch ally of the Belarusian opposition and has even hosted some of its exiled leaders.

Vilnius’ stance on China is also a product of its established loyalties. Upon announcing its withdrawal from the project, Vilnius said the differences between EU and non-EU countries in the group created conflicting interests that were often “too hard to manage.” Like other Baltic states, Lithuania is dependent on the EU for market access and on NATO and the U.S. for its security. Befriending a competitor of the EU and U.S. was simply too risky.

The diplomatic spat comes at a time when the EU is finding it increasingly difficult to balance its own economic priorities with member states’ growing concerns about China’s insufficient transparency and disinformation campaigns. As the bloc tries to gain more access to the Chinese market, European capitals are becoming increasingly critical of Beijing’s attempts to weaponize their dependence on Chinese medical supplies and of China’s crackdowns in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. These are some of the reasons China was labeled a “systemic rival” of the bloc in an EU policy paper back in 2019.

Geopolitical Futures

Earlier this month, a diplomatic row erupted between China and an unlikely European nation. It began back in May, when Lithuania decided to leave the 17+1 initiative, a project established in 2012 by Beijing to strengthen ties to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Then, in July, the government in Vilnius said it would allow Taiwan to establish a representative office in Lithuania under its own name, rather than “Chinese Taipei,” a decision Beijing criticized as a violation of its “one China” policy. In response, on Aug. 10, Beijing recalled its ambassador to Lithuania and asked that Vilnius recall its ambassador to China. A week later, it also suspended freight train service to Lithuania.

This may seem like a minor spat between Beijing and a relatively minor European country, but as a member of the European Union, Lithuania’s foreign policy moves have broader implications for the bloc. Its dispute with Beijing could make it harder for the EU to reach consensus on how to manage its relationship with China. But for Beijing, that’s a good thing. It benefits from divisions that prevent the EU from forming a unified front against it. That’s why, even as its relations with the Baltic states grew increasingly tense, its relations with other EU members – namely, Hungary and Poland – as well as the Western Balkans were getting stronger. In these places, China sees an opportunity to expand a growing wedge and strengthen its foothold in Europe.

China and the EU

Under China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative, the 17+1 format was designed as a way for Beijing to build economic ties to Central and Eastern Europe through investments and promises of better access to the Chinese market. Since the program's inception, however, China’s involvement in the region hasn’t been balanced across all the participants.

The project includes many of the same countries involved in the Three Seas Initiative, a NATO-backed alliance spanning the Baltic, Black and Adriatic seas focused on strengthening regional cooperation. The Three Seas project supports the development of economic infrastructure – financed by private and public (including EU) funds – that’s critical to NATO’s strategy to counter Russian influence along its current containment line. For China, therefore, the 17+1 initiative was a way to balance other external powers that already had a strong foothold in the region – mainly the EU but also Russia and the United States.

Beijing has been eager to partner with European countries that want to keep their foreign policy options open. Chief among them has been Hungary, which is likely China’s closest ally in the region. Earlier this month, Budapest awarded two Chinese firms – China Civil Engineering and China Railway 11th Bureau – contracts to complete upgrades on a railway connecting Hungary to Serbia – just the latest Hungarian deal for Chinese financing. Hungary is an important ally to China because of its willingness to defy Brussels on a number of fronts. Hungary has a long history of balancing between powers – most notably the West and Russia, but increasingly also China. By avoiding siding with one power over any other, Budapest has found that it can reap the most benefits.

Poland is another country with which China is developing closer ties. Like Hungary, Poland has had a contentious relationship with Brussels over issues relating to the rule of law and EU values. In the past, Poland has been wary of getting too close to China because of its strategic relationship with the United States, but since the start of this year, its relations with Beijing have improved. According to the Polish Economic Institute, Poland was among the top destinations in the EU for Chinese investment in 2020, totaling an estimated $1 billion. Bilateral talks have also intensified. Polish Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau visited China in late May – just weeks after the U.S. waived sanctions on a consortium tasked with building the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, a project that will bring Russian natural gas to European markets and that Poland opposes. Warsaw’s overtures to Beijing are meant to send a message to Washington that it needs to continue to engage with its traditional allies in Eastern Europe.

The timing of Rau’s visit, just after Lithuania announced its decision to leave the 17+1 grouping, was convenient for China. It allowed Beijing to stem the fallout from the announcement and prove that it’s still engaged in the region. For China, building ties to Poland is only one element of a broader strategy to rebalance its increasingly uneasy relationship with the EU and keep the public engaged with the Communist Party’s agenda internally.

Lithuania said its decision to pull out of the initiative stemmed from the fact that it didn’t see any increase in access to the Chinese market, despite Beijing’s promises. That China is not among Lithuania’s top trading partners made it easier for Vilnius to make the move. Other EU members have also signaled their displeasure with the initiative – Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Romania and Slovenia chose to send ministers instead of heads of state to the last 17+1 summit in February – but none have left the group so far.

Lithuania’s spat with China had been brewing for a while. Last November, its parliament voted to replace Chinese tech firm Huawei with Sweden’s Telia Company in the country’s 5G network, and in May, the parliament passed a resolution condemning Beijing’s treatment of Muslim minorities as “crimes against humanity.” The resolution came two months before Lithuania announcement it would allow Taiwan to open a representative office under its own name in Lithuania.

Why would Vilnius choose to take a stand against Beijing now? In part, it’s because Lithuania is concerned about Beijing’s growing interest in its neighbor, Belarus, which is not part of the now-16+1 initiative. Since 2015, China and Belarus have grown closer both economically (through the provision of Chinese loans) and politically. Last year, Chinese media followed Russian media in characterizing mass anti-Lukashenko protests as an attempt at a Western-backed “color revolution.” Chinese media were also critical of the EU’s decision to impose sanctions on Belarus after its forced landing of a commercial plane en route to Lithuania in Minsk to arrest a dissident journalist. Lithuania has long been a staunch ally of the Belarusian opposition and has even hosted some of its exiled leaders.

Vilnius’ stance on China is also a product of its established loyalties. Upon announcing its withdrawal from the project, Vilnius said the differences between EU and non-EU countries in the group created conflicting interests that were often “too hard to manage.” Like other Baltic states, Lithuania is dependent on the EU for market access and on NATO and the U.S. for its security. Befriending a competitor of the EU and U.S. was simply too risky.

The diplomatic spat comes at a time when the EU is finding it increasingly difficult to balance its own economic priorities with member states’ growing concerns about China’s insufficient transparency and disinformation campaigns. As the bloc tries to gain more access to the Chinese market, European capitals are becoming increasingly critical of Beijing’s attempts to weaponize their dependence on Chinese medical supplies and of China’s crackdowns in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. These are some of the reasons China was labeled a “systemic rival” of the bloc in an EU policy paper back in 2019.

Comments

-

China and the Rest of Europe

While most Eastern European countries are most interested in growing their exports to China, Beijing’s interest with this group has been focused on building infrastructure. Chinese investment targets transportation, energy and telecommunications, supporting China’s ambitions to extend its reach to faraway markets and, more important, to gain significant levers in a contested region. Investment in the manufacturing sector has usually been linked to supporting investment in infrastructure. In EU countries, such investment needs to meet environment and transparency rules, a complicating factor for China.

By contrast, the Western Balkans is wide open to large Chinese investment projects. Beijing can also engage more directly with Western Balkan governments without worrying about EU regulations getting in the way. In short, the decision-making process is much easier and, in general, getting to know the right person can get you a better deal.

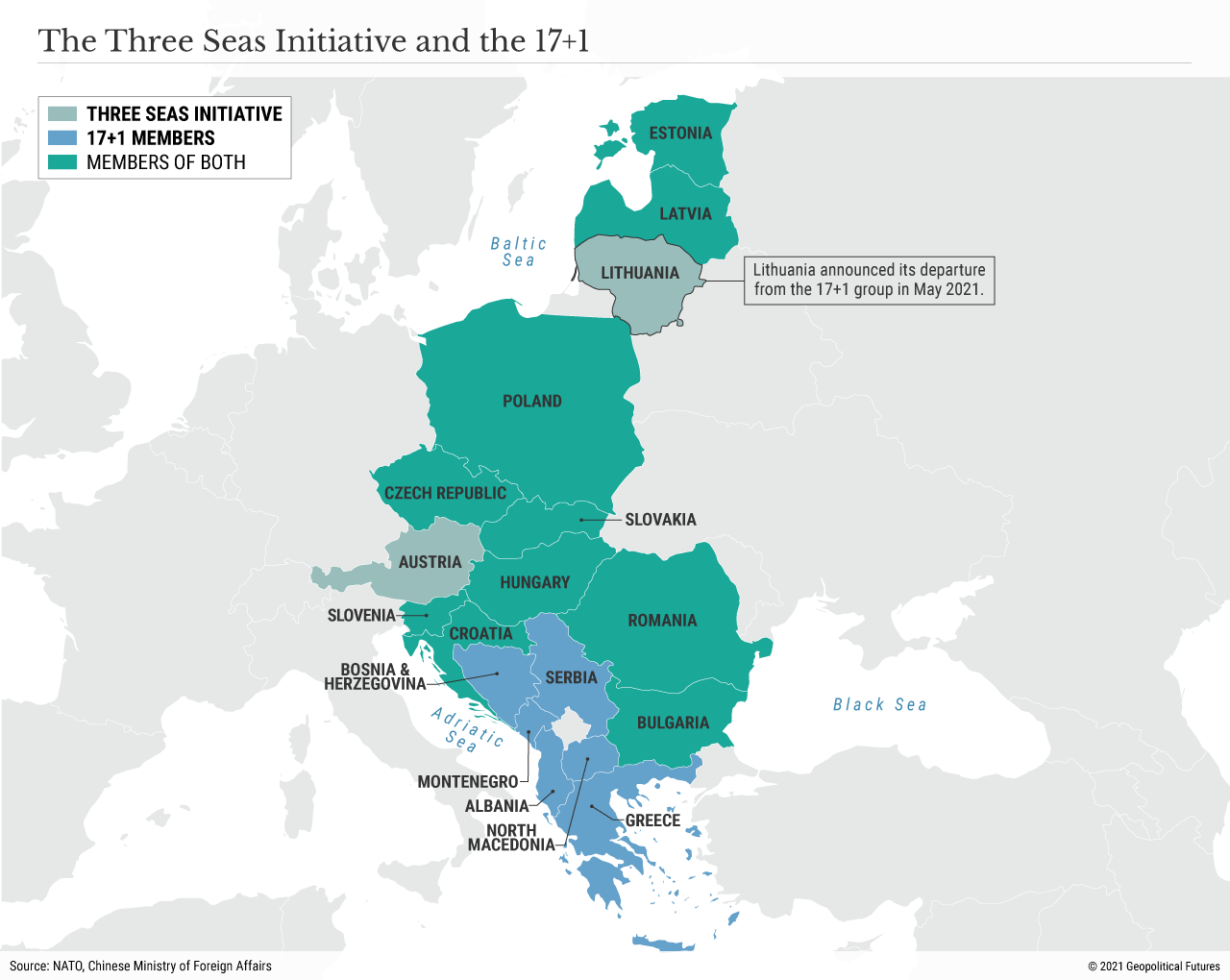

This is particularly important for Beijing because its investment decisions are not only about business but also about expanding its footprint around the globe. Chinese financial flows don’t only come in the form of foreign direct investment but also as development loans, grants, mergers and acquisitions, and long-term concession agreements. This makes it difficult to assess the dependency of these countries on China. According to the most recent data reported by the region’s central banks, financial flows between China and the Western Balkans between 2009 and 2019 were worth about $13.5 billion. Two-thirds of this happened during the past five years, a period in which Chinese FDI has grown significantly; FDI stocks increased to around $2 billion in 2019 from $100 million in 2009.

Most of these transactions are managed through intergovernmental agreements and not through private Chinese companies. Less than 1 percent of the turnover of Central and Eastern Europe is controlled by private Chinese firms. It is the Chinese government, operating through the country’s army of state-owned enterprises, that manages flows. Not only do Chinese investors receive direct support from the Chinese government and utilize loan facilities from Chinese state-owned banks, but, considering existing intergovernmental agreements, they also receive preferential treatment in public procurement tenders, finding themselves as the sole bidders for infrastructure projects.

While the West criticizes the Western Balkans for the lack of transparency that enables corrupt regional governments to prioritize deals that enrich their support networks, China sees the weak governance standards and corrupt practices as an advantage. Local politicians prefer Chinese loans to EU funding, because the latter is conditional on better governance and structural reforms.

Recently, however, Montenegro has become emblematic of the debt problems a country may face after taking up a large loan from China without considering the risks. In 2014, Montenegro borrowed $1 billion to fund the first portion of a 163-kilometer (101-mile) highway to Serbia. After the first 41 kilometers were completed, Montenegro had to ask the EU to help with repayment and try to negotiate an extension with Beijing. As a result of the project, Montenegro’s debt exposure to China as a share of GDP is about 18.5 percent. China holds approximately a quarter of Montenegro’s total debt, which reached 103 percent of GDP in 2020. The terms of the loan say China could seize property in the event of default, as it did in Sri Lanka, where a Chinese state-owned enterprise received a 99-year lease for a strategically located Chinese-financed port after the country fell behind on repayment. -

Other countries in the region, like Bosnia-Herzegovina or North Macedonia, have also been on the receiving end of China’s so-called debt diplomacy. These loans not only build China’s economic influence, but they also complicate the recipient countries’ efforts to implement structural reforms needed to receive EU funding and eventually to become EU members.

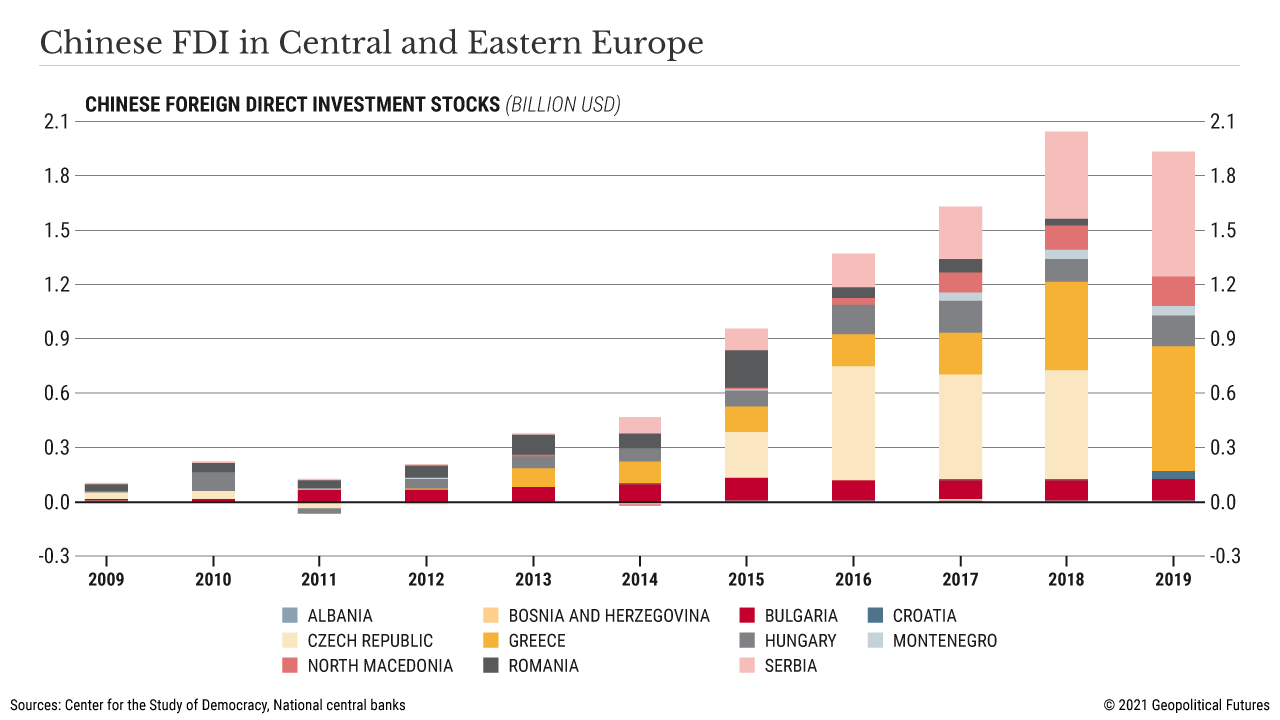

Serbia has been the most welcoming country to Chinese investment. More than half of all Chinese projects by value in the 16+1 group are located in Serbia. Most involve the building of major transport infrastructure, including construction of parts of the EU’s Pan-European transport system (the Corridor X railway and highway sections, Corridor XI highway, and the Mihajlo Pupin bridge and the Belgrade metro network). Chinese companies have also bought some of Serbia’s largest industrial complexes, including the Smederevo steel plant and the Bor copper mining and smelting complex. China has invested to modernize two of Serbia’s largest lignite-fired power plants, the Kostolac B3 and Kolubara B power stations. These investments provide substantial numbers of jobs, which shore up public support for China. As a result, Serbia was an early recipient of China’s COVID-19 vaccines, and it’s common to hear Serbians talk about the greatness of China and how Beijing will help rebuild their country’s economy. For China, Serbia is the Western Balkans’ most important market and the closest hub to the EU.

Conversely, Albania reports the least investment from China. This is because Albania has experience with China’s influence, having been the only Chinese satellite state in Europe during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. As a result of that history, Tirana is cautious of Chinese goodwill. In October 2020, Albania was one of 39 countries to sign a U.N. statement denouncing China for its treatment of ethnic Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang and for curtailing freedoms in Hong Kong. Nevertheless, Albania has not yet withdrawn from the 16+1 grouping.

China the Savior?

The EU’s enlargement fatigue and the pandemic’s tendency of making states focus on problems closer to home present an opportunity for China to fill the void in the Western Balkans. Russia’s internal problems over the last decade have forced it to reduce its own funding and investment in the region. Old Russian friends like Serbia have developed good ties with China in the meantime. Projects in countries like North Macedonia, a NATO member and longtime aspirant to EU membership, are ongoing. The Montenegrin debt issue is worrisome, but the population blames the government more than it blames Beijing. During the past year, China has sent aid to fight the pandemic throughout the region, increasing its public visibility.

-

The lack of economic progress and the socio-political instability of the Western Balkans make it susceptible to the influence of an outside power promising salvation. Until recently, the EU was expected to be the savior, providing funding for the reconstruction after the wars of the 1990s while demanding reforms to shore up democratic rule. Others hoped the U.S. would lend a hand, and still others thought Russia could be a better ally on security matters.

The hope of EU membership is fading, so these countries are left to look to Russia and China for help. Russia has its own problems, but China seems ready and willing to step in. Although China isn’t an immediate challenge to the EU, U.S. and Russia in the region, its influence is growing and will work to its advantage. At the same time, Beijing portrays these relationships at home as important steps toward achieving the ultimate Chinese dream of a central role for China on the world stage. -

The Throbber likes Lithuania in this one.