Welcome to the Hardcore Husky Forums. Folks who are well-known in Cyberland and not that dumb.

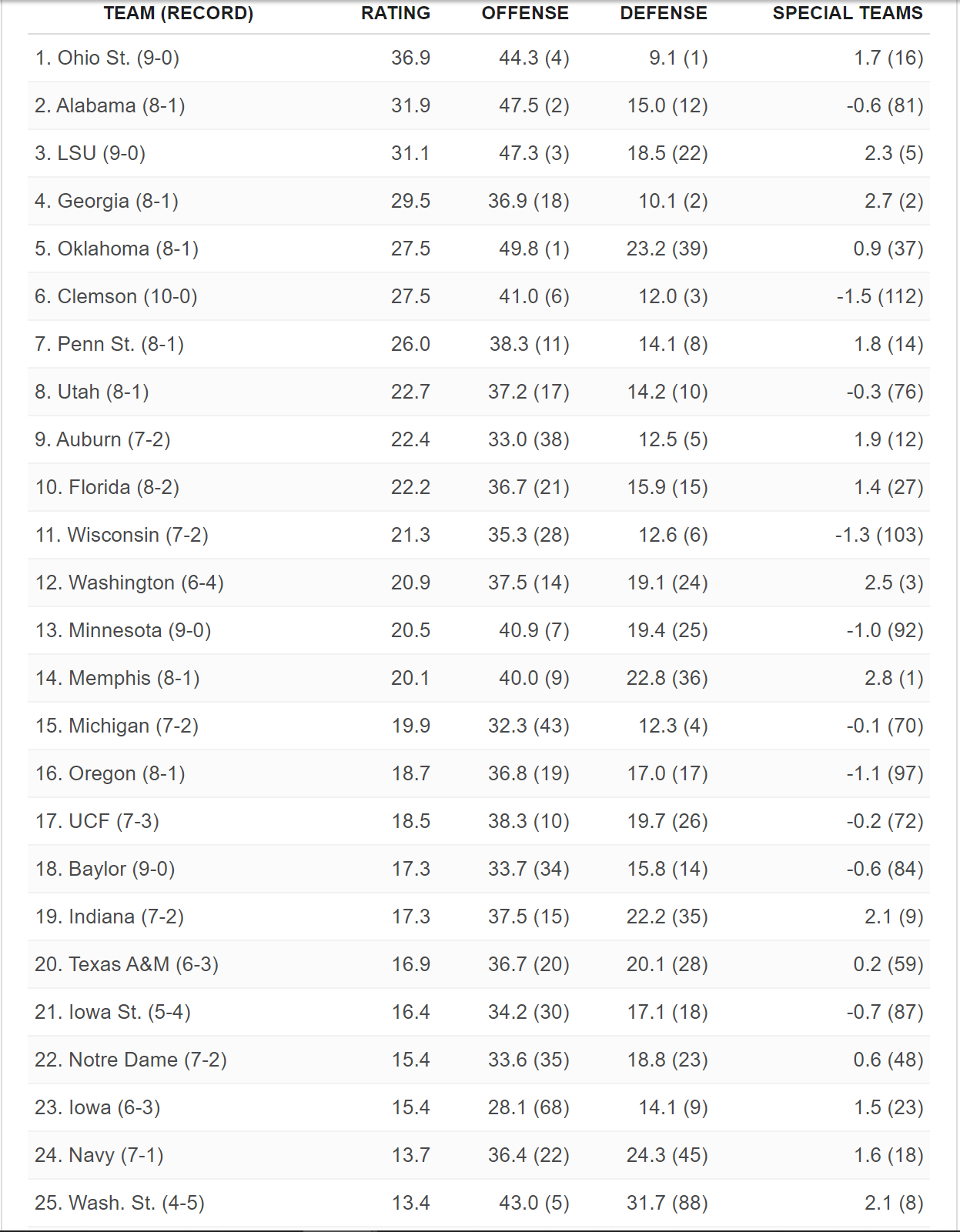

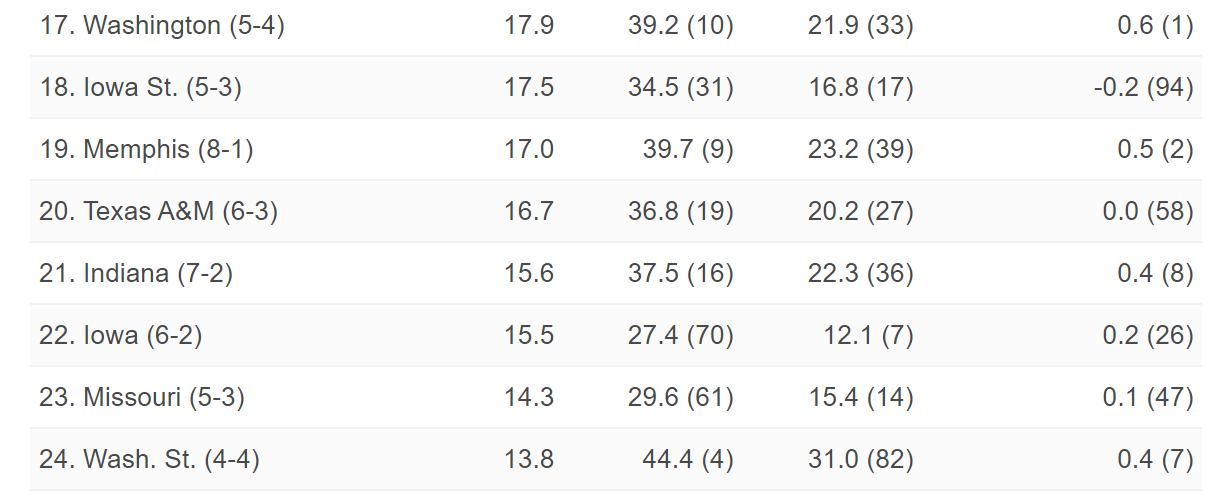

SP+ rankings are baffling

Comments

-

This is the kind of shit you'd see from a Jim Mora team. Probably even worse. 5-3 is an abject failure. Even if we're to go on a run and finish 10-3, the season is still a massive disappointment. A QB like Eason is what typically puts a team over the top into title contention. We've completely squandered that opportunity.

-

Are you saying there’s a chance to win an offseason natty during the season?BleachedAnusDawg said:Looks like we're making a late push to get in to the S+P playoffs!

Chincredible! -

https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/27940007/sp+-rankings-week-9-lsu-catch-ohio-state-alabama

Officially #1 in the nation, in special teams. Woo! -

I usually agree with you but I struggle to see where good defense is going to come from. The LBers next year will be an abortion. Unless Calvert is super uber stud or something?RoadDawg55 said:

This. Defense will be good next year, but if Eason doesn’t come back the offense will suck. Then we basically have to wait for Huard and he actually has to be good early on. Nothing guaranteed at all.Neighbor2972 said:Neither the offense or the defense completely suck, they just aren't good enough to make plays when you need them to.

Our defense has carried our offense the last few years, this year Eason is bailing out our bad offense, next year the defense will improve but our offense will suck. An endless cycle of being one piece away. -

The impact of making every field goal is just impossible to overstate.

If this is for real and we have two more years of it in store we knight maybe actually do something one day. -

Winning on Tableau >>>>>>> Winning on the Field

-

They will still be at least somewhat weak at LB. everywhere else should be good. DL could even be great, especially if Levi returns.Swaye said:

I usually agree with you but I struggle to see where good defense is going to come from. The LBers next year will be an abortion. Unless Calvert is super uber stud or something?RoadDawg55 said:

This. Defense will be good next year, but if Eason doesn’t come back the offense will suck. Then we basically have to wait for Huard and he actually has to be good early on. Nothing guaranteed at all.Neighbor2972 said:Neither the offense or the defense completely suck, they just aren't good enough to make plays when you need them to.

Our defense has carried our offense the last few years, this year Eason is bailing out our bad offense, next year the defense will improve but our offense will suck. An endless cycle of being one piece away. -

Best 4 loss (and 3 loss) team in the country, rather easily. suck it cuougz

-

4whlinder said:

Only metric I needHuskyClaws said:3 losses

-

Why play the games when we have computers? This is getting ridiculous lol