Welcome to the Hardcore Husky Forums. Folks who are well-known in Cyberland and not that dumb.

After Afghanistan’s Fall, Watch Turkmenistan

DerekJohnson

Administrator, Swaye's Wigwam Posts: 70,336

in Tug Tavern

The insular Central Asian country could attract refugees and extremists.

By: Ekaterina Zolotova

Last week as the Taliban surged into Kabul, effectively completing their takeover of Afghanistan, attention in surrounding states and major Eurasian powers turned to a different mass movement that was only just beginning: the surge of Afghan refugees out of the country. Massive refugee outflows will strain neighboring economies and societies, and could spread the threat of terrorism to states with little capability to defend themselves. One such state, the weakest of Afghanistan’s neighbors, is Turkmenistan – a country rich in energy resources and poor in military capabilities. Ashgabat’s vulnerabilities will likely force it to abandon its long-standing preference for neutrality, kicking off a competition for influence among its more powerful neighbors.

Fortress Turkmenistan

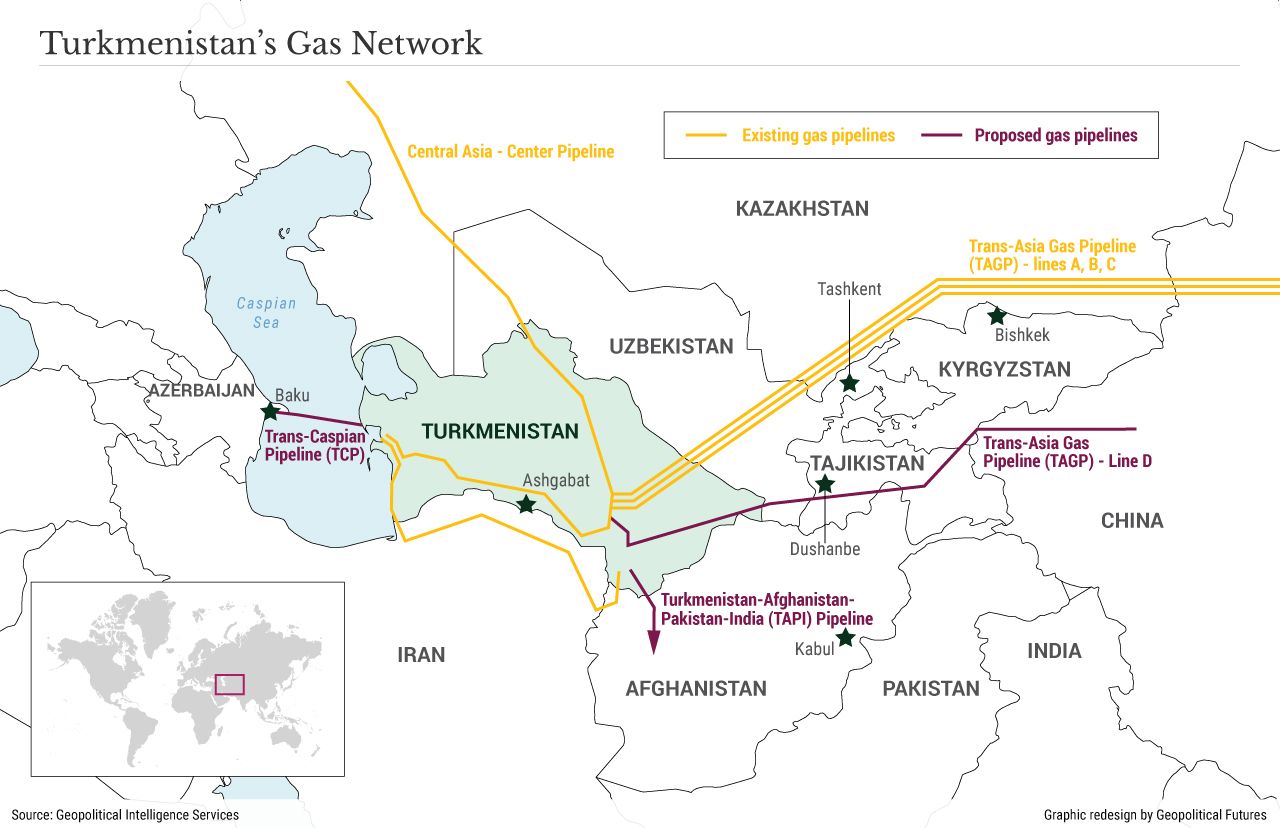

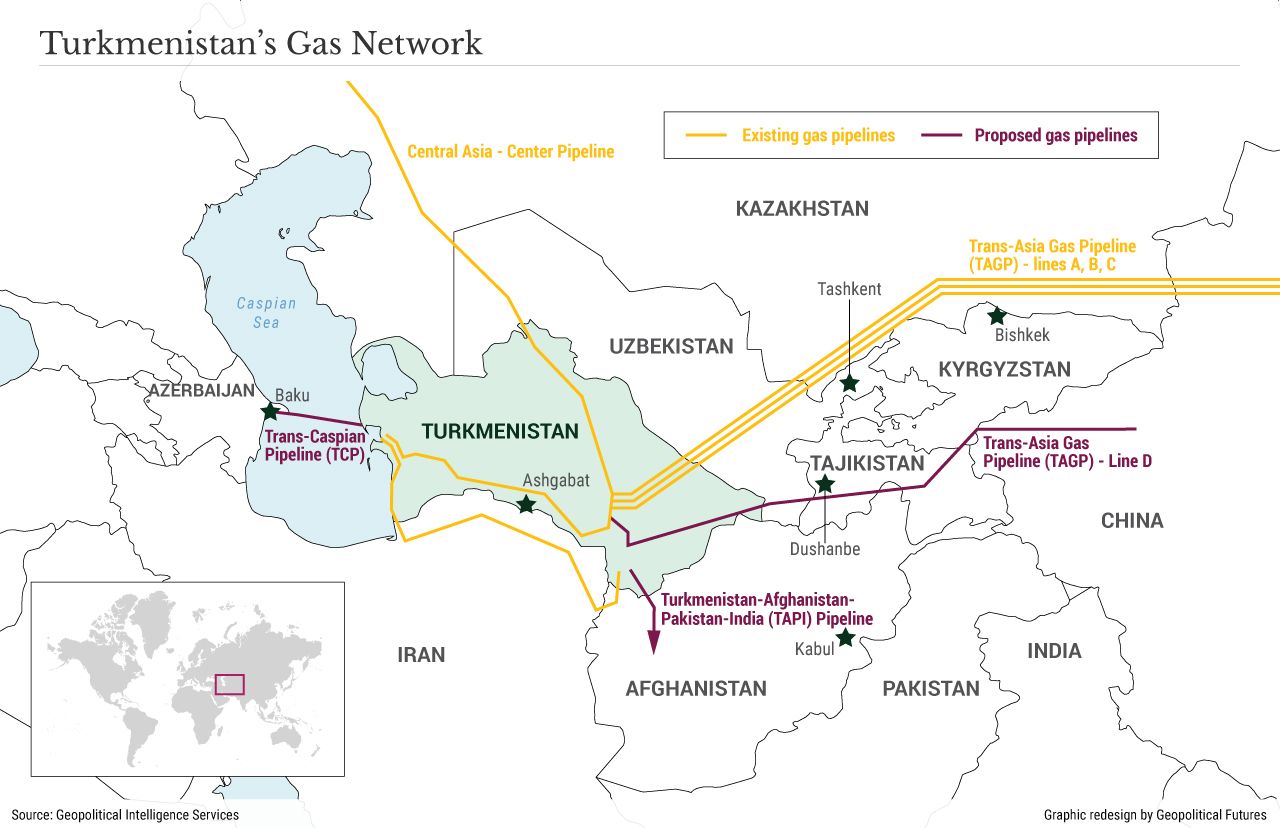

Turkmenistan is landlocked, but it has significant energy resources and is a valuable transit state in Central Asia. From north to south it forms part of the link between Russia and the Persian Gulf, and from west to east it lies along the route between Europe and the rest of Central Asia. It has the fourth-largest proven gas reserves in the world and is part of the so-called strategic energy ellipse, which combines the hydrocarbon reserves of the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf. Unsurprisingly, Turkmenistan is a flashpoint for regional powers: Russia wants to reassert its influence in the post-Soviet space; Iran shares a long border with Turkmenistan as well as centuries-old cultural and historical links; Turkey is interested in strengthening its political, ideological and economic positions in the region; and China wants access to its cheap energy resources.

But Turkmenistan is notoriously reclusive and secretive, and reliable information about it is hard to come by. (For example, officially it has not had a single case of COVID-19.) It is the most insular and authoritarian of all the post-Soviet states, a product of its difficult situation after the breakup of the Soviet Union. Post-Soviet Turkmenistan is resource-rich but population-poor; it has the second-most territory but the fewest people among the five Central Asian republics. Ashgabat participates in regional trade and sends its students to study abroad, but its political and military neutrality annoys key partners who would like to see Turkmenistan as their ally. It is not a member of any of the regional economic or political groupings, such as the Eurasian Economic Union and the Commonwealth of Independent States (it is an associated member of the latter group), and it avoids military organizations and alliances like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Collective Security Treaty Organization. This allows Turkmenistan to preserve its sovereignty and avoid giving too much influence to an outside power.

New Destination

The collapse of the Afghan government threatens to burst the bubble Turkmenistan has crafted around itself. The inflow of Afghans and ethnic Turkmens, who make up the sixth-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, could pose a far greater threat to Turkmenistan than to other countries in the region precisely because of Ashgabat’s weak economy and system of rigid political control.

Already the Turkmen authorities are preventing Afghans and ethnic Turkmen from crossing the border into their territory, but it’s unclear how long they can hold out. Neighboring Uzbekistan built a barrier along its relatively short border with Afghanistan, the most heavily guarded border in the world. The Tajik-Afghan border is reinforced by the constant presence of Russian troops conducting joint exercises. The Turkmen army lacks the capabilities of its Pakistani and Chinese counterparts, and at any rate its border with Afghanistan is about 800 kilometers (500 miles) and runs through flat plains, which are hard to police yet easy to cross. Much of its military equipment, remnants of the Soviet era, is likely inoperable. Modernization efforts have been inadequate, and the personnel are rumored to be poorly trained and unskilled.

Making matters worse, Turkmenistan has for years suffered chronic food shortages, hard currency shortages and high unemployment, and its budget – which depends on energy exports – is strained. Its economic crisis began many years ago, partly as a result of lost gas revenue due to the termination of its contract with Gazprom in 2016 (the supply agreement was renegotiated in April 2019), as well as hyperinflation and several lean years. Coronavirus restrictions pushed food prices higher, which especially hurt regions that depend on other parts of the country for their supply of vegetables and fruits. Ashgabat introduced coupons for flour, butter, sugar and other basic goods, but even these subsidized products are becoming unaffordable, and there’s rising discontent in some regions over the way local authorities have distributed the subsidies. Opposition figures, especially those living in exile abroad, have criticized the government for its poor handling of the pandemic, natural disasters and the economy.

In Need of Friends

A big influx of refugees could only destabilize the economy further and fuel protests. And in fact, Turkmenistan’s fragility, lack of natural barriers, and enormous gas reserves and pipeline infrastructure could attract those who want to spread terrorism and extremism.

The Turkmen economy is built around energy exports: Almost 90 percent of all its exports consist of energy products, accounting for nearly a quarter of its gross domestic product. But Turkmenistan’s major gas fields are located close to the Afghan border. Moreover, Turkmenistan plays a central role in the network of gas pipelines covering Russia, China and Iran, and is key to plans for a trans-Caucasian gas pipeline to Europe as well as projects to supply gas to India via Afghanistan and Pakistan. Notably, the Taliban support this latter project, known uncreatively as the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, since they themselves are interested in a consistent source of energy, but it’s unclear how exactly they plan to protect the infrastructure within Afghanistan if opposition to their return swells. Moreover, other participants in the pipeline may not take kindly to giving the Taliban a role in the project or seeing the Taliban spread their influence beyond Afghanistan’s borders. Given its precarious situation, Turkmenistan can’t afford threats to these pipelines.

Turkmenistan’s diplomatic policy is to be friendly with everyone. It maintains regular contacts with Russia, China, Iran, Turkey and Taliban representatives to ensure the security of its borders, and it describes the relationship between the Afghan and Turkmen peoples as fraternal. But Ashgabat is ill-equipped to prevent the spread of extremism and instability across its borders. This was not a significant challenge as long as the U.S. military was in Afghanistan, but now the economic and security situations have turned against Turkmenistan, and its neutrality is not an asset. Alignment with Russia, Iran, Turkey and/or China could enhance the security of the country, but only if its leaders are prepared to abandon their long-standing policy of neutrality. They probably do not have a choice. The competition for Turkmenistan will soon begin.

By: Ekaterina Zolotova

Last week as the Taliban surged into Kabul, effectively completing their takeover of Afghanistan, attention in surrounding states and major Eurasian powers turned to a different mass movement that was only just beginning: the surge of Afghan refugees out of the country. Massive refugee outflows will strain neighboring economies and societies, and could spread the threat of terrorism to states with little capability to defend themselves. One such state, the weakest of Afghanistan’s neighbors, is Turkmenistan – a country rich in energy resources and poor in military capabilities. Ashgabat’s vulnerabilities will likely force it to abandon its long-standing preference for neutrality, kicking off a competition for influence among its more powerful neighbors.

Fortress Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan is landlocked, but it has significant energy resources and is a valuable transit state in Central Asia. From north to south it forms part of the link between Russia and the Persian Gulf, and from west to east it lies along the route between Europe and the rest of Central Asia. It has the fourth-largest proven gas reserves in the world and is part of the so-called strategic energy ellipse, which combines the hydrocarbon reserves of the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf. Unsurprisingly, Turkmenistan is a flashpoint for regional powers: Russia wants to reassert its influence in the post-Soviet space; Iran shares a long border with Turkmenistan as well as centuries-old cultural and historical links; Turkey is interested in strengthening its political, ideological and economic positions in the region; and China wants access to its cheap energy resources.

But Turkmenistan is notoriously reclusive and secretive, and reliable information about it is hard to come by. (For example, officially it has not had a single case of COVID-19.) It is the most insular and authoritarian of all the post-Soviet states, a product of its difficult situation after the breakup of the Soviet Union. Post-Soviet Turkmenistan is resource-rich but population-poor; it has the second-most territory but the fewest people among the five Central Asian republics. Ashgabat participates in regional trade and sends its students to study abroad, but its political and military neutrality annoys key partners who would like to see Turkmenistan as their ally. It is not a member of any of the regional economic or political groupings, such as the Eurasian Economic Union and the Commonwealth of Independent States (it is an associated member of the latter group), and it avoids military organizations and alliances like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Collective Security Treaty Organization. This allows Turkmenistan to preserve its sovereignty and avoid giving too much influence to an outside power.

New Destination

The collapse of the Afghan government threatens to burst the bubble Turkmenistan has crafted around itself. The inflow of Afghans and ethnic Turkmens, who make up the sixth-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, could pose a far greater threat to Turkmenistan than to other countries in the region precisely because of Ashgabat’s weak economy and system of rigid political control.

Already the Turkmen authorities are preventing Afghans and ethnic Turkmen from crossing the border into their territory, but it’s unclear how long they can hold out. Neighboring Uzbekistan built a barrier along its relatively short border with Afghanistan, the most heavily guarded border in the world. The Tajik-Afghan border is reinforced by the constant presence of Russian troops conducting joint exercises. The Turkmen army lacks the capabilities of its Pakistani and Chinese counterparts, and at any rate its border with Afghanistan is about 800 kilometers (500 miles) and runs through flat plains, which are hard to police yet easy to cross. Much of its military equipment, remnants of the Soviet era, is likely inoperable. Modernization efforts have been inadequate, and the personnel are rumored to be poorly trained and unskilled.

Making matters worse, Turkmenistan has for years suffered chronic food shortages, hard currency shortages and high unemployment, and its budget – which depends on energy exports – is strained. Its economic crisis began many years ago, partly as a result of lost gas revenue due to the termination of its contract with Gazprom in 2016 (the supply agreement was renegotiated in April 2019), as well as hyperinflation and several lean years. Coronavirus restrictions pushed food prices higher, which especially hurt regions that depend on other parts of the country for their supply of vegetables and fruits. Ashgabat introduced coupons for flour, butter, sugar and other basic goods, but even these subsidized products are becoming unaffordable, and there’s rising discontent in some regions over the way local authorities have distributed the subsidies. Opposition figures, especially those living in exile abroad, have criticized the government for its poor handling of the pandemic, natural disasters and the economy.

In Need of Friends

A big influx of refugees could only destabilize the economy further and fuel protests. And in fact, Turkmenistan’s fragility, lack of natural barriers, and enormous gas reserves and pipeline infrastructure could attract those who want to spread terrorism and extremism.

The Turkmen economy is built around energy exports: Almost 90 percent of all its exports consist of energy products, accounting for nearly a quarter of its gross domestic product. But Turkmenistan’s major gas fields are located close to the Afghan border. Moreover, Turkmenistan plays a central role in the network of gas pipelines covering Russia, China and Iran, and is key to plans for a trans-Caucasian gas pipeline to Europe as well as projects to supply gas to India via Afghanistan and Pakistan. Notably, the Taliban support this latter project, known uncreatively as the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, since they themselves are interested in a consistent source of energy, but it’s unclear how exactly they plan to protect the infrastructure within Afghanistan if opposition to their return swells. Moreover, other participants in the pipeline may not take kindly to giving the Taliban a role in the project or seeing the Taliban spread their influence beyond Afghanistan’s borders. Given its precarious situation, Turkmenistan can’t afford threats to these pipelines.

Turkmenistan’s diplomatic policy is to be friendly with everyone. It maintains regular contacts with Russia, China, Iran, Turkey and Taliban representatives to ensure the security of its borders, and it describes the relationship between the Afghan and Turkmen peoples as fraternal. But Ashgabat is ill-equipped to prevent the spread of extremism and instability across its borders. This was not a significant challenge as long as the U.S. military was in Afghanistan, but now the economic and security situations have turned against Turkmenistan, and its neutrality is not an asset. Alignment with Russia, Iran, Turkey and/or China could enhance the security of the country, but only if its leaders are prepared to abandon their long-standing policy of neutrality. They probably do not have a choice. The competition for Turkmenistan will soon begin.

Comments

-

What are Mohammed the rug merchants thoughts